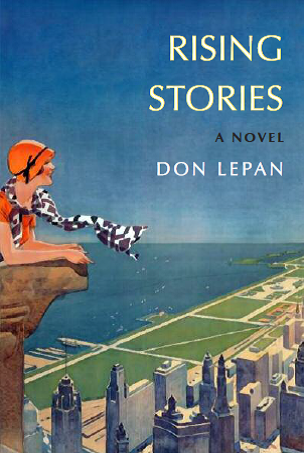

The initial idea for Rising Stories came to me in December of 2009 as Maureen and I were reading a letter to the Globe and Mail about the sorts of imaginary worlds that children discover when they go through doors in magical closets or down magical rabbit holes. What sort of world would we imagine for ourselves if we were writing such a story? The thought came to me of a child pressing the buttons of one of the elevators in a skyscraper; rows of additional numbers suddenly appear—and magically, those additional stories turn out to be real.

But what or who would be up there?

I’m not entirely sure how or why I came to think within a few months of someone like P.K. Page inhabiting this magical world—but if I put my mind into analytic rather than imaginative mode I can think of a few possibilities. The rising stories of the skyscraper are from one angle a metaphor for growing up, and that growing up in which physical growth mirrors mental growth is followed (if we’re lucky) by growth of a different and purely invisible sort—the growth of mind, of feeling, of wisdom. From this angle it makes a certain sort of sense for the child to travel up to find a very old person in a space that you can't at first see.

In the case of K.P. in Rising Stories, there is a further wrinkle, quite aside from the question of whether or not the story on which she lives is real: it is not at all clear that she is real. Robin remembers at one point that she has died: is the person Robin meets in her apartment on the 86th story a ghost? Or some other sort of magical figure? Or simply a figment of Robin’s imagination, and Robin’s memory?

(As an aside here, I might mention that, at about Robin's age, I had a similar experience involving the death of an aunt. I think I had felt guilty for not having sent her a thank-you note or some such thing; when I was told that she had died I pushed the information from my mind, preferring to think of her as still alive; I did not "remember" that she was in fact dead for many months.)

P.K. Page died on January 14, 2010. You would not think that the death of someone in her 94th year would inspire shock and a tremendous sense of loss. If you make it to your 93rd birthday still able to get around a little and with your wits more or less about you, (as P.K. certainly had most of hers), and you die a death that does not entail prolonged and horrendous physical pain, we generally think it has to be counted good news—a good end to a good life. The fact that I (and I’m sure many others) nevertheless did feel a very powerful pull in the heart on the news of her death, a feeling of pained shock as well as deep sadness, attests to the extraordinary warmth of feeling P.K. inspired—and also, I suppose, to her having come to seem almost ageless. Of course she looked old in her last few years, but far less old than she was. And she retained an extraordinary vitality, as well as real elegance—an elegance not at all the product of fancy clothes or jewelry or makeup. “In the strangest of ways, she was beautiful” is what Robin thinks when the door opens.

P.K. was a well-known painter as well as an acclaimed poet, and I wanted the story of a painter to be part of Rising Stories.

As well, I may have thought of P.K. in part because she represented to me bookends of my own experience. She had known my family in the 1950s in Ottawa, when both her husband and my father worked in the Department of External Affairs, and I was a very small child—too young to remember her. Roughly fifty years later, as a book publisher, I contacted P.K. about her inclusion in an anthology and she encouraged me to be in touch if I ever came to Victoria. I did exactly that, and between 2005 and 2009 paid her visits on several occasions when I was in the city. She would always welcome me with a strong gin and tonic, but take vodka herself; she explained that she would prefer gin but that, for some medical reason, vodka had come to agree with her more in her old age. (Those who have read Rising Stories may at this point be reminded that, although Robin never sees K.P. eating anything, the child does comment on the “colorless liquid” that she drinks.) And she would always provide wonderful conversation—about aging and about love, about the oddities of the human spirit, and of course about writing books—mostly the many books she was still writing, for children as well as for adults, but also my own Animals, which she was kind enough to read in manuscript, and which (as she later wrote) led her to give up eating meat.

The character of K.P. in Rising Stories is inspired by P.K., not based on her. The story of collapsing skyscrapers in Brazil is lifted from P.K.'s Brazilian Journal, and P.K. did say (as K.P. does) that she felt she had aged more in her 91st year than all the other 90 put together. But I don’t believe P.K. was particularly interested in skyscrapers—and she had no more lived in one than I ever have. She was a painter of a very different sort than is K.P. And K.P.’s voice is not that of P.K., either, though I do think there are echoes of the one in the other. I hope to always hear those echoes.

Sunday, October 25, 2015

Sunday, October 18, 2015

Against Our Way of Celebrating Thanksgiving

[Canadian Thanksgiving is over for another year; American Thanksgiving approaches. The piece below--a short work of speculative dystopian fiction rather than a conventional essay--is not specific to either one of these. The year is 2215, and the gniebs now control earth; the gnieb who is the author of the essay below is addressing the issue of what moral status should be accorded the creatures who were once themselves the dominant species on the planet---the humas, as they are now referred to.Oct 20, 2215

The story was published recently in The Navigator. ]

I know this will be an unpopular argument: I want to speak out against something we have come to accept as part of our community values, as part of our traditions of sharing.

Some may say the matter I bring before you is a trivial one, one that pales beside the great issues of our day. Scientists warn that our “progress” has put at risk our great forests, our waterways, our atmosphere—indeed, almost every part of our environment. Increasingly, we are told that a war involving the entire planet is a real possibility. In the big picture, you may say, can it seriously be suggested that the condition of our food animals is an issue meriting our attention?

This is where I beg to differ. Rest assured, I am no extremist: I make no call for the food animals to be “freed” or for we gniebs to eat nothing but plants. There is simply no case to be made for radical views of that sort. That’s an obvious point, perhaps, but let us not forget the evidence on which it is based. Following the conquest, test after test after test established beyond a doubt that the intelligence level of gniebs is far above that of humas—so much so that it would be ludicrous to suggest that humas be accorded the same moral status as gniebs. And of course no responsible person does suggest they be accorded such status: I mention all this merely in order to make it abundantly clear that, in what I am about to say, I am no extremist. Though I will in a moment be defending the “interests” of humas—I would not for a moment suggest they be accorded “rights.”

These preliminaries dispensed with, let me go directly to the main point. If there is one thing in this culture on which all parties may relied on to agree, it is the value of community—and of sharing. For neighbors to show respect and consideration for each other—to give each other the benefit of the doubt, to work together to keep neighborhoods clean and safe for our children, to support local initiatives as much as national and international ones, to extend a welcome to families new to the neighborhood. And, of course, for gniebs of all backgrounds to gather together to celebrate Thanksgiving with their families. That is for us a central ritual—a ritual that honors our shared history and all that we share in our national community, that honors as well the community that goes beyond national borders, and that honors the sanctity of life itself.

There are of course those who believe that the values of individual striving are more important than those of community—but no one is against community, no one is against sharing. The left will always put a different twist on the idea than does the right, of course. To those on the right the values of community and of sharing are more a matter of tradition; those on the left put more emphasis on sharing as a form of egalitarianism. But no one is against sharing per se.

I declare myself here and now to be against one form of sharing. I am opposed to the very foundation on which our tradition of Thanksgiving dinner has come to rest. More specifically—and I do want to be specific—I am opposed to the cruelty that underlies our treatment of the humas, whose consumption has become such a central part of our ritual of sharing at Thanksgiving.

When we conquered this planet all those centuries ago—and in the process, it seems safe to say, saved the humas from extinction—we gniebs were faced with a set of very difficult questions. Perhaps the most difficult was how to deal with the humas, who had themselves been so dominant for so long. Should we simply consign them wholesale to oblivion, as they themselves, whether through negligence of through willful slaughter, had often consigned their own inferiors—from Beothuk to Bo to Bororo, from auk to passenger pigeon to rhinoceros. Or should we make a place for them in what would now become a better world—a world of gnieban values, of gnieban striving, of gnieban sharing?

We chose the second, of course. Humas were not subjected to wholesale slaughter. They were raised to be productive throughout their useful lives; huma life was put into the service of higher values.

But at what cost? Here it is essential to distinguish between the practices of our ancestors and those that have become prevalent in our own day. When gniebs first domesticated the humas we treated them well—virtually every authority is agreed on that point. (Too well, many might say.) Their lives might be taken and their blood spilled, but as a rule that occurred at the end of their productive lives—and/or in harmony with the natural cycles of harvest and of thanksgiving. Throughout their productive lives they were treated with dignity, even with kindness, in some sense as fellow creatures. They tilled our soil, they tended our crops—and, at the end of their productive lives, their meat graced our tables, and we gave thanks together for the sacrifice of their lives.

Is there anything that can equal the sense of true sharing that comes at Thanksgiving time? Family and friends gathered around the table to celebrate the season, and to give thanks for that sacrifice. Its value is deeply moral, but deeply spiritual as well—even those of us such as myself who belong to no organized religion can sense the spiritual significance of that sacrifice, that sharing. I may even suggest that such traditions extend to the animals themselves, the animals who share themselves with us. We cannot understand their gibberish, of course, but perhaps we may imagine their own gratitude—imagine their own sense of sharing themselves, in gratitude for having been given fruitful lives, lives without suffering. It is to honor that tradition, not to sully it that I ask you to remember how those humas in bygone days were treated throughout their productive lives—with dignity, even with kindness, as our fellow creatures.

And their milk? That is arguably a more complex question, but once the nutritionists weighed in and informed us of how healthful humas’ milk was compared to our own, we could hardly be blamed for arranging a system such as that which survives to the present day. (Humas themselves, of course, are known to have put into place a very similar system with a four-legged species that is believed to have become extinct not long before our arrival on the planet.) By removing the young from the mother, she may be induced to produce more milk, which the superior species may then consume. The young are of course the unfortunate victims of the process, but so long as their end is brought about quickly and without cruelty, there can be no ethical objection—any more than there can be any reasonable objection to ending any huma life quickly and without cruelty.

The problem with all this—at long last I come to the main point—is that we have not held to these values. Not by any stretch of the imagination. Under the name of “tradition” we bring to the table humas that are nothing like the humas of old. I leave to one side the matter of taste—though I confess I can find nothing in the taste of today’s factory farmed huma to compare with the sweet and slightly gamy taste that I can still remember from when I was young. But it is not taste that should concern us—it is morality. Readers may not wish to know the truth, but know it they should. Today’s humas live lives that are hideous to contemplate. They are no longer to be seen in the open fields, of course, where robotic devices now perform almost every task once assigned to humas. We no longer see them. They live behind closed doors in vast sheds, cramped, confined, and generally in chains; it is only for their milk and flesh that we value them now. The udders of those bred for the dairy industry—their breasts, as once we called them—are painfully distended as a result of the way we have bred them, bred them to produce more and more milk that can be sold at lower at lower prices. So too the bellies of those bred to gain weight quickly and reach the table as soon as possible; the weight we have bred into them is intensely painful to carry.

There is more, much more—I believe that most of you who are reading this may have some dim awareness of everything I'm speaking of, a dim awareness you would perhaps rather push from your conscious mind. I sympathize with your desire not to know the details; I do not want to paint for you an endless series of pictures of suffering animals wallowing in their own excrement—animals that are bound in due course for our dinner tables. It is enough to be aware of the general picture.

Once we know that, it is surely unconscionable not to take some action. To be blunt, it is unconscionable to continue to eat these products of cruelty. If we are to continue, on this and on every Thanksgiving, to glorify the harvest and to accept with grace the humas sacrificed at this special time, we must honor the traditions some of us remember from the time when we were young, when meat and milk were not the products of cruelty, when the traditions of sharing and of sacrifice did not entail needless suffering on the part of humas or of other animals, imposed through our own cruelty, throughout the full duration of their lives. We must return to the practices of the past—to a time when we could eat Thanksgiving dinner with a clear conscience, knowing we were consuming the products of kindness rather than of cruelty. We owe it to the animals; even more importantly, we owe it to ourselves.

“But what of the poor?” I hear some of you say. I own this to be a serious problem. If it is the case (as I believe it to be) that the mistreatment of humas has led to great reductions in the prices of animal foodstuffs, what are we do about prices if conditions for humas are ameliorated—if the efficiencies of breeding and of mechanization are rolled back, if the animals are allowed to lead more or less natural lives up until slaughter? If no other measures are taken, that could surely place an intolerable burden on the poor.

Of those who accept my case that we must address the cruelties that have become part and parcel of modern farming, there are no doubt a few who will say forget about the poor. They have only themselves to blame for their poverty, and they deserve no better. There are surely a few at the other end of the political spectrum who will say we should eat lentils and leaves, all of us, nothing but lentils and leaves; we should leave the humas and all the other animals alone. We need not adopt either of these ludicrous extremes: let me propose a sensible middle ground. Just as it would be unreasonable to insist we all get our protein from legumes rather than from meat and milk, it would be unreasonable to insist that the poor do so. But let us recognize that eradicating cruelty to humas cannot be done for free; the meat and the dairy products will all have to carry higher prices—and that, unless we provide subsidies, the poor will indeed bear that burden disproportionately. That, then, is exactly what we should do—provide income assistance to those who require it. Such subsidies will prevent the poor from slipping into worse poverty, while allowing the animals—the huma animals—to live lives that are no longer filled with endless suffering.

So there it is—a modest proposal for our families, for our communities, and for our world to depart from today’s traditions of sharing and of thanksgiving by returning to an older set of traditions, a set of traditions that did not rest, as ours does today, on an unacknowledged foundation of cruelty.

No, this is not so important an issue as that of how to avoid war, or how to save our environment from destruction. But if we are to judge ourselves as superior to the other creatures—morally superior, not simply more intelligent—then we must listen to our better selves. We must refrain from unnecessary cruelty. We must reject the false tradition of sharing that is reliant on that cruelty. We must return to the great traditions of sharing and of sacrifice that were once the foundation of our society. We can—and we must—re-establish gnieban society on that great tradition of true sharing.

Labels:

cruelty to animals,

dystopia,

gniebs,

modest proposal,

Thanksgiving,

turkey,

vegan fiction

Wednesday, October 14, 2015

Copyright, the TPP, and the Canadian Election

The message below was composed with the Broadview Press e-list in mind (and sent earlier today). I'll post it here as well, in the hope that it may be of interest to others.Late last week it became known that the TPP trade agreement would significantly increase copyright restrictions in Canada.

Let me begin by filling in a bit of the background for those who may not be aware of it. The 1990s were a time of triumph for the many large corporations who continually seek to extend copyright restrictions. In 1995 the UK (along with the rest of the European Union) increased the duration of copyright from 50 to 70 years following the death of the author. In 1998, pressed by the Disney Corporation and others, the US followed suit, increasing the duration of copyright in America to 95 years after publication (for works published in 1978 or earlier) and to 70 years following the death of the author (for works published thereafter). Later, Australia and other nations also moved from 50 to 70 years.

But a few holdouts in the developed world remained—Canada and New Zealand among them—and as we have moved further into the twenty-first century it has sometimes seemed that the tide might be turning. More and more people have argued that it is both unwise and unfair to keep works from entering the public domain for more than three generations following an author’s death. Copyright restrictions have an undeniable value when they allow authors to control the rights to their works and to be compensated for the time that has gone into the creative process. Copyright also ensures that publishers are able to justify their investments in the publication and promotion of new books; without the temporary grant of an exclusive copyright license there would be little incentive to create new works. But copyright has always been intended as a temporary license that must be balanced against the public good of a public domain. Unlimited, or excessively long, copyright terms have often kept scholars from publishing (or even obtaining access to) material of real historical or cultural significance. They have severely restricted certain options for university teaching as well. Broadview’s editions of Mrs. Dalloway and of The Great Gatsby (edited by Jo-Ann Wallace and by Michael Nowlin, respectively), for example, are to my mind unrivalled. Each includes far more than just the text itself: explanatory notes, extended introductions, and an extraordinary range of helpful and fascinating background material in a series of appendices. They offer a truly distinctive pedagogical option. But instructors and students in the USA are still not allowed access to those editions.

Currently, we at Broadview are looking at publishing similar editions of works by other authors who have been dead for more than 50 but fewer than 70 years—works such as Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984, for example; a Broadview edition of such works, with the appendices of contextual materials that are a feature of almost every Broadview edition, would provide highly valuable context for students at all levels. We are also looking forward to January 1, 2016, when we will finally be able to make the superb Broadview edition of The Waste Land and other Poems—with its excellent explanatory notes and extensive range of background material on modernism—available in Canada. (Eliot died in 1965.)

Until now Canada’s government has insisted that it would retain a “made-in Canada” copyright policy. This past week, though, it signed the Trans Pacific Partnership trade agreement.

Nowhere in the information made public by the Canadian government about the TPP are we informed of any change in the 50-year rule. Last Friday, however, the text of the intellectual property provisions was leaked; it has now been revealed that the TPP agreement will force Canada and other countries that had resisted the push toward longer copyright restrictions to fall into line with the American and European Union standards. (The news was revealed on the blog of law professor Michael Geist, with whom I’ve often disagreed over other copyright issues—notably, the appropriate interpretation of the education-related provisions of the Canadian Copyright Act—but to whom we are I think indebted in this instance. See http://www.michaelgeist.ca/2015/10/canada-caves-on-copyright-in-tpp-commits-to-longer-term-urge-isps-to-block-content/ . Here is a link to the full text of the intellectual property provisions in the TPP agreement: https://wikileaks.org/tpp-ip3/WikiLeaks-TPP-IP-Chapter/WikiLeaks-TPP-IP-Chapter-051015.pdf )

If the legislatures of the governments involved ratify the agreement, the public domain will be cut back by a full 20 years in Canada, New Zealand, and Malaysia; those countries will be forced to extend copyright restrictions from 50 to 70 years following the death of the author.

If the TPP is approved in Canada, then, say goodbye to those Orwell and Eliot editions. Indeed, given that the application would appear to be retroactive in Canada, say goodbye to a number of books that we’ve been making available in Canada for some time already; we at Broadview will have to take them off the market until the authors have been dead for the full 70 years. The newly-published Broadview editions of Dorothy Richardson’s Pointed Roofs and The Tunnel? It seems likely that we would be forced to take them out of circulation in Canada until 2027; though the works were published in 1915 and 1919 respectively, Richardson died in 1957.

Looking forward, how significant would the effect be? Let’s look at just one year—at some of the authors who died in 1970, and some of the classic works they published. Among them are Erich Maria Remarque (author of All Quiet on the Western Front, first published in 1929); E.M. Forster, author of A Passage to India, first published in 1924; and Bertrand Russell (author of The Problems of Philosophy, first published in 1912). Under the current law, we could publish Broadview editions of these works on January 1, 2021; even the current law, in other words, creates an effective monopoly in these cases for roughly a century after initial publication. If the TPP is approved, the situation becomes far more extreme. Each of these early twentieth-century works would not enter the public domain in Canada until at least 2040.

And for scholars seeking to publish historically important hitherto-unpublished material that might be controversial and that, for whatever reason, a copyright holder might prefer to keep under wraps? The new rule would be 70 years from date of creation. The Group of Seven artist Lawren Harris died in 1970; under current Canadian law it will become possible to make any of his unpublished papers available to the public at the end of 2020. Under the TPP, a Lawren Harris letter from 1969 that his estate did not wish to see enter the public domain could remain under wraps until the end of 2040.

Everyone has heard a great deal of the TPP provisions regarding auto parts and dairy products. Yet we have been told nothing of a change so important as this on copyright; no doubt the Canadian government is aware that it would not improve its already-low standing in the polls by announcing more restrictive copyright laws.

How many other hidden provisions are there in the TPP? The Canadian election is in less than a week, and we have no idea.

I should perhaps own that I was a supporter (in some respects a reluctant supporter, but a supporter nonetheless) of both the 1988 Free Trade Agreement and the subsequent NAFTA treaty involving Mexico, the US, and Canada. I cannot support the TPP. Justin Trudeau says that he and the Liberals are neither for nor against this deal. Stephen Harper’s Conservatives will continue to defend it vigorously without telling Canadians all the specifics of what is in it. For Canadians opposed to the TPP there are two options available; both the Greens and the New Democrats have come out against the deal. Of these, of course, only the New Democrats have a realistic chance of forming (or being part of) a government.

I now know how I will be voting on October 19.

Sunday, October 4, 2015

Let's Refuse to Give Mass Murderers the Publicity They Crave

John Hanlin is the sheriff of Douglas County, Oregon, where last Thursday's mass murder of at least nine people took place. He took an extraordinary stance after the killings:

From the assassinations of a long line of politicians, to the 1989 École Polytechnique massacre, to the Columbine High School killings, to the Utøya island mass murder in Norway in 2011, and through to the events in Oregon last week, we keep splashing the names and photos of the killers across our front pages and our television screens. Why can we not simply say, “The killer, whose name cannot be revealed, was a 26-year old Caucasian with a history of instability and an avowed dislike of organized religion." No name, no photo, and no chance of becoming famous through committing deranged acts of violence. If news organizations feel they have a responsibility to dig deeper, fine. But do so without revealing the name, without publishing the picture. Surely that's not too much to ask.

Our laws already recognize one important circumstance (youthful offenders) that we regard as providing sufficient justification to trump freedom-of-speech principles when it comes to revealing names; it’s time to add another.

But even if legislators can't manage to change the laws governing media coverage, the media themselves can start to behave responsibly--act in the way that Sheriff John Hanlin recommends, not in the way that the mass murderers are counting on.

[NB Part of the above also appeared in "Remaining Nameless," which was posted in this blog following last October's attack on the Canadian parliament.]

Let me be very clear: I will not name the shooter. I will not give him credit for this horrific act.... [I encourage the media to] "avoid using [the shooter's name], repeating it, or engaging in any glorification and sensationalizing of him. ... He in no way deserves it. Focus your attention on the victims and their families and helping them to recover.Hanlin is surely right--and not only as a matter of what the shooter and his victims deserve. It's also a matter of deterring future such acts. As Doug Saunders ("Lone Wolf" - The Globe and Mail, Oct. 25, 2014) and various others have pointed out, sensational acts of violence are often in large part motivated by a hope on the part of a mentally deranged person that the violent act will make him (it is almost always a him) famous. The Oregon shooter was quite explicit about this. In the message he left for the world before committing his heinous act he commented on the perpetrator of the recent TV station murders in Virginia:

I have noticed that people like him are all alone and unknown,, yet when they spill a little blood, , the whole world knows who they are. ... Seems the more people you kill, the more you're in the limelight.And we play right along. After reporting on Friday morning the sheriff's plea not to name the shooter, NPR named the shooter. In the front page article quoting the shooter's comments about killing people to get "in the limelight," The New York Times published his name and picture.

From the assassinations of a long line of politicians, to the 1989 École Polytechnique massacre, to the Columbine High School killings, to the Utøya island mass murder in Norway in 2011, and through to the events in Oregon last week, we keep splashing the names and photos of the killers across our front pages and our television screens. Why can we not simply say, “The killer, whose name cannot be revealed, was a 26-year old Caucasian with a history of instability and an avowed dislike of organized religion." No name, no photo, and no chance of becoming famous through committing deranged acts of violence. If news organizations feel they have a responsibility to dig deeper, fine. But do so without revealing the name, without publishing the picture. Surely that's not too much to ask.

Our laws already recognize one important circumstance (youthful offenders) that we regard as providing sufficient justification to trump freedom-of-speech principles when it comes to revealing names; it’s time to add another.

But even if legislators can't manage to change the laws governing media coverage, the media themselves can start to behave responsibly--act in the way that Sheriff John Hanlin recommends, not in the way that the mass murderers are counting on.

[NB Part of the above also appeared in "Remaining Nameless," which was posted in this blog following last October's attack on the Canadian parliament.]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)